-

Architects: Cafer Bozkurt Architecture

- Area: 935 m²

- Year: 2011

-

Photographs:Cengiz KARLIOVA, Ahmet ERTUG, Ergin IREN, Sibel OZKARS

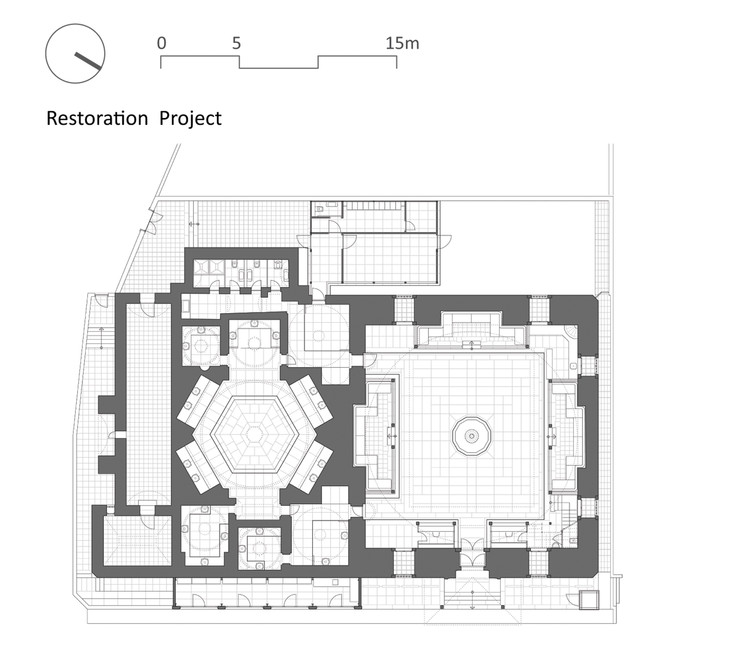

Text description provided by the architects. The Kılıç Ali Paşa Hamam was constructed in 1580 by Master Architect Sinan, on behalf of Ottoman Admiral Kılıç Ali Paşa as part of a larger ‘külliye’ complex, in the Tophane district of Istanbul. As the physical manifestation of a unique period in the historical harbor of the Ottoman imperial city, the Kılıç Ali Paşa hamam has become not only part of public space again in the Tophane area, but also part of an overall revitalization of a previously derelict area in the city. 430 years of layered materials and debris, literally ‘embalming’ the surfaces and ‘burying’ the structure, had to be removed in order to identify and restitute the original Sinan building, thus relinking this 1st degree historical monument back to its origins.

The architecture of the Hamam is mostly characterized by its authentic masonry construction, lead roof cladding on the domes, and use of natural stone on the interior. Damage of the main structural walls, domes and arches was mainly due to the weathering effects of water, frost, vegetation and lack of maintenance. Many heavy layers of cement, plaster, bitumen and tiles had replaced most of the original lead-cladding and severely damaged the 16th-century brickwork. This unnatural weight destroyed the building’s structural integrity, led to asymmetric settling and thus made it more susceptible to the damaging effects of numerous earthquakes.

This project incorporates custom construction techniques, such as traditional stonemasonry, woodworking and lead roof-workmanship, as well as the use of original building materials to preserve the original character of the structure. Custom-made bricks, traditional ornaments, special windows and the unique ‘horasani’ mortar mixture were designed and produced specifically for this building.

In terms of new constructions and materials used in the Hamam, contemporary design and aesthetic compatibility of new and old was key, such as the zinc cladding and steel construction used in the new service addition in the back garden. The former water storage and original heating space is correspondingly converted into the modern technical center utilizing new mechanical and electrical installations without damaging the original architecture. Natural ventilation is used for the exchange of used air to the outside and circulation of fresh air within the building. The skylight on top of the main dome of the camegah allows used air to rise and flow out, thus forcing cool outside air to be drawn into the building naturally through window openings in the lower areas.

Great spatial deformation happened over the centuries inside the entrance-dressing space underneath the main dome. In the 16th-century interior, there were only stone divan platforms set against the walls where visitors would sit, hang their clothes on hooks and relax after bathing. Over time, demand for private places to dress and leave belongings influenced the interior architecture. Wooden dressing rooms were added, finally culminating in a full two-storey wood construction built in the 1950’s, concealing the interior walls and architectural details.

A crucial decision in this project was to recover the original Sinan period spatial experience underneath the main dome by removing these dominant 20th century additions. On the ground floor, the stone platforms are now fully visible and outfitted with seating and relaxing areas, thus regaining their lively social function, supported by kitchenette and service functions in the corners. A respectful mezzanine floor, built of solid oak and housing private dressing areas is featured above.

Finally, the Kılıç Ali Paşa Hamam shows a successful case of holistic thinking, considering the building as a whole, rather than just assessing individual elements. Never veering away from scientific methodology and bringing together specialists of various scientific fields (art and architectural historians, archaeologists, chemists), the Kılıç Ali Paşa restoration has succeeded in exposing an original Sinan piece and has brought a delightful Ottoman monument into the contemporary cultural spotlight.